Brands aren’t immune to cancel culture… or are they? 63% of Nigerians will patronize a brand even if they disagree with it

The Issue

Cancel culture particularly sprouted and dug in its tentacles in the year 2020 as celebrities, brands, and even pancake mixes were getting cancelled right, left, and centre. In the midst of a global epidemic, the Black Lives Matter demonstration, and a nationwide protest against police brutality and racial injustice, people took to social media to declare a number of well-known celebrities and brands—from J.K. Rowling to Netflix—officially “over”.

Aunt Jemima syrup was an example of a brand subjected to the wrath of the mob of justice. People called out the fact that the brand’s origins were “based on a racial stereotype”. The brand’s management had already acknowledged this, and the design had already been altered numerous times, including the removal of Aunt Jemima’s handkerchief. Still, with George Floyd’s death still burning hot in people’s minds, people were quick again to remember the brand’s racial ties and called for its ‘cancellation’. As a result, Quaker announced that their eponymous Aunt Jemima syrup would be renamed Pearl Milling Company and given a new logo.

In addition, in August and September, the hashtag “Cancel Netflix” trended on Twitter in response to how the streaming service marketed the foreign-language film “Cuties.” The film is about a teenage girl who emigrates to France and joins a dance team to rebel against her previous culture. On the other hand, Netflix viewers were critical of the film’s promotion, which appeared to sexualize the youngsters by portraying them twerking as part of their dancing moves. Netflix changed their advertising materials and apologized for how the matter was handled, but Twitter users can still be heard in the echo of the night chanting ‘cancel Netflix!’

Nigerian brands were not particularly exempt from this wave of cancellation. Global telecommunications brand, MTN, found itself as a victim during the #EndSARS protest in October 2020. It was purported that the communications brand had intentionally killed its network during the Lekki Tollgate Shootings and was in cahoots with the Nigerian military. Many Nigerians urged for a company boycott, claiming it is solely interested in fattening its coffers and pursuing selfish goals. MTN, on the other hand, has continued to thrive in the Nigerian market. By the end of 2020’s third quarter, the company recorded a 13.9% boost in its total revenue, achieving a total revenue of N975. 76 billion in the year, which raises the question of whether cancel culture is a legitimate phenomenon with any impact.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, what is cancel culture?

Cancel culture refers to the widespread practice of withdrawing (cancelling) support for public personalities and businesses after they have done or said anything regarded objectionable or offensive. It is complicated in that it both questions and enacts power structures. Some say that cancel culture is too final, claiming that it eliminates opportunities for learning from mistakes and altering habits. On the other hand, others point out how cancel culture is committed to providing space for individuals to criticize dominant and oppressive norms, ideas, institutions, and, yes, even people.

Still, is cancel culture as popular in Nigeria as it is in other (foreign) communities? And how much of an impact does it really have on brands?

The Question

According to an Edelman research, 64% of customers worldwide will buy or boycott a company purely based on its stance on a social or political issue. Only a few years ago, the word “boycott” was associated with the extreme margins of society. However, boycotting has now become a typical consumer response. It isn’t just directed at socially irresponsible businesses but also applies to companies perceived to project false social and environmental efforts and intentions.

Critics see cancel culture as a modern-day version of the evil mob. Last year, at least 150 writers, including JK Rowling and Malcolm Gladwell, signed a letter that denounced cancel culture as a danger to free expression. But, increasingly, we are beginning to see that cancel culture particularly affects brands just as much.

According to an 8,000-person study conducted in 2018, consumers feel that businesses are a more potent driver for societal change than the government. More than half of the respondents (53%) felt that brands can do more to alleviate social evils than the government, and 54% said that it is simpler to persuade businesses to address social issues than it is to get the government to act. As a result, much more pressure is placed on brands to be responsible for their actions and words.

Maarten Lagae, Executive director of Landor & Fitch declares that it is important brands have clear cut principles when it comes to handling cancel culture.

“It’s incredibly important you know what you stand for, and what your values and principles are, and use that as your guiding light not just for marketing campaigns, but for everything you do. That’s from the people you hire to the behaviours you reward, products you launch, the way you talk and how you interact with people. It’s not necessarily having contingency plans or communications ready for an event where you may get cancelled, but what is it we want to stand for and what we believe in,” he states.

What are Nigerians’ thoughts on businesses being boycotted in the name of ’cancel culture’? Do they believe that ‘cancel culture’ is a force for good, or do they believe that ostracizing businesses that do things they don’t agree with is a problem?

What The Streets Are Saying

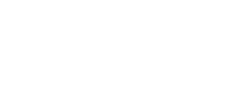

Among our national focus group, 47% think that cancel culture is simply people being held accountable for their actions, and that it’s not a bad thing, hence cancel culture is not a problem. On the other hand, 53% of the respondents opined that people are being unfairly cancelled and that society needs to be more forgiving.

The question of whether brands should be ‘cancelled’ for acting in any way that offends one’s sensibilities was rather polarizing, as, 43% said ‘no’ and 40% said ‘yes’. Some respondents opined that brands should be given a chance and a platform to right their wrongs and explain their perspectives. A few also made a case for brands being run by “humans who make mistakes”, and that unless these actions are committed consistently, they should be given second chances.

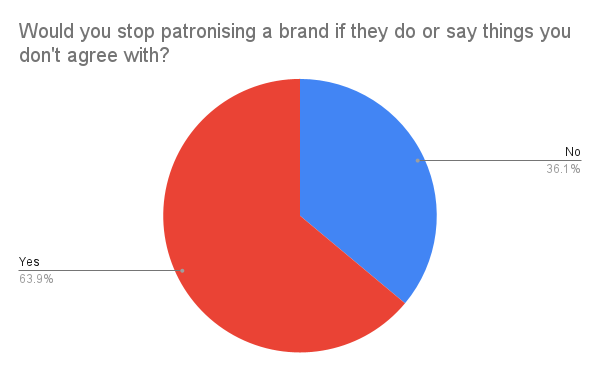

An overwhelming majority (63%) of Nigerians stated that they would not stop patronising a brand if they do or say things they don’t agree with. Whilst 37% posited that they would in fact stop patronising a brand if they don’t agree with its actions. A total of 56% stated that a major characteristic of ‘cancel culture’ is the boycotting of brands.

Interestingly, more Nigerians (50%) believed that the effect of such boycotts has a huge effect on brands and 46% stated that the effect was minimal. A smaller number of people (3%) believed that cancel culture does not affect brands at all. Some respondents believe that as long as a product is good, it should be purchased, adding that a lot of the cancel culture movement is motivated by a vindictive and biased mob. “A good product is a good product. And often, cancel culture creates a situation where the effort of multitudes are disregarded because of the punitive intentions of individuals or isolated groups. Further, the perspective that leads to ‘cancelling’ seems often controlled by a sponsored biased media,” a respondent pronounced.

Another commenter pointed out that because corporations have numerous brands under their roof, they aren’t truly affected by cancel culture. As a result, when one of the brands is ‘cancelled’, it has little impact because the firm continues to earn from other brands. She points out that “cancel culture is a good way to hold brands accountable, but that deep down when faced with buying decisions, people don’t really boycott these brands.”

Joju Aladegbongbe, a brand expert, discussed the phenomenon and how Nigerian businesses should deal with it.

“A brand should revamp, rebrand or lay low for a while. However, a brand with a distinct brand vision should not be as affected. For example, there was a time Nike could have been cancelled because of the Colin Kaepernick ambassadorship, they weren’t. Because they knew their brand and what they stood for, it worked in their favour. It depends on you as a brand, what it is you are about. In the long run, cancel culture does not really affect any brand, only if the brand is posturing and acting like something they are not.”

Nike’s choice to make Colin Kaepernick the face of their TV and print advertising campaign drew a lot of criticism. Before an NFL game, the American quarterback knelt during the national anthem to protest police brutality, and he was criticized for supposedly disrespecting the flag. Despite this, Nike made Kaepernick an ambassador with the slogan: “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything. Just Do It”. Some people chose to boycott Nike and deface its merchandise on social media. However, consumer efforts to kill the brand were plainly unsuccessful, as Nike’s market value increased by $6 billion. The brand made a smart move by using Kaepernick and his philosophy to reaffirm what the brand stood for. This backs up Aladegbongbe’s assertion that knowing your brand and methodically planning your communications in that line are the keys to being prepared.

According to the findings of our nationwide poll, the idea of cancel culture is divisive among Nigerians. However, the majority of them would never genuinely boycott a brand, preferring instead to patronize it as long as it is excellent. As a result, cancel culture can only impact a brand to the extent that the brand allows it. A brand with a strong identity, values, and ideals will undoubtedly withstand the test of time and the cancel-ready fingers of millennials and Gen-Z’rs.